Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust by Belzberg Architects

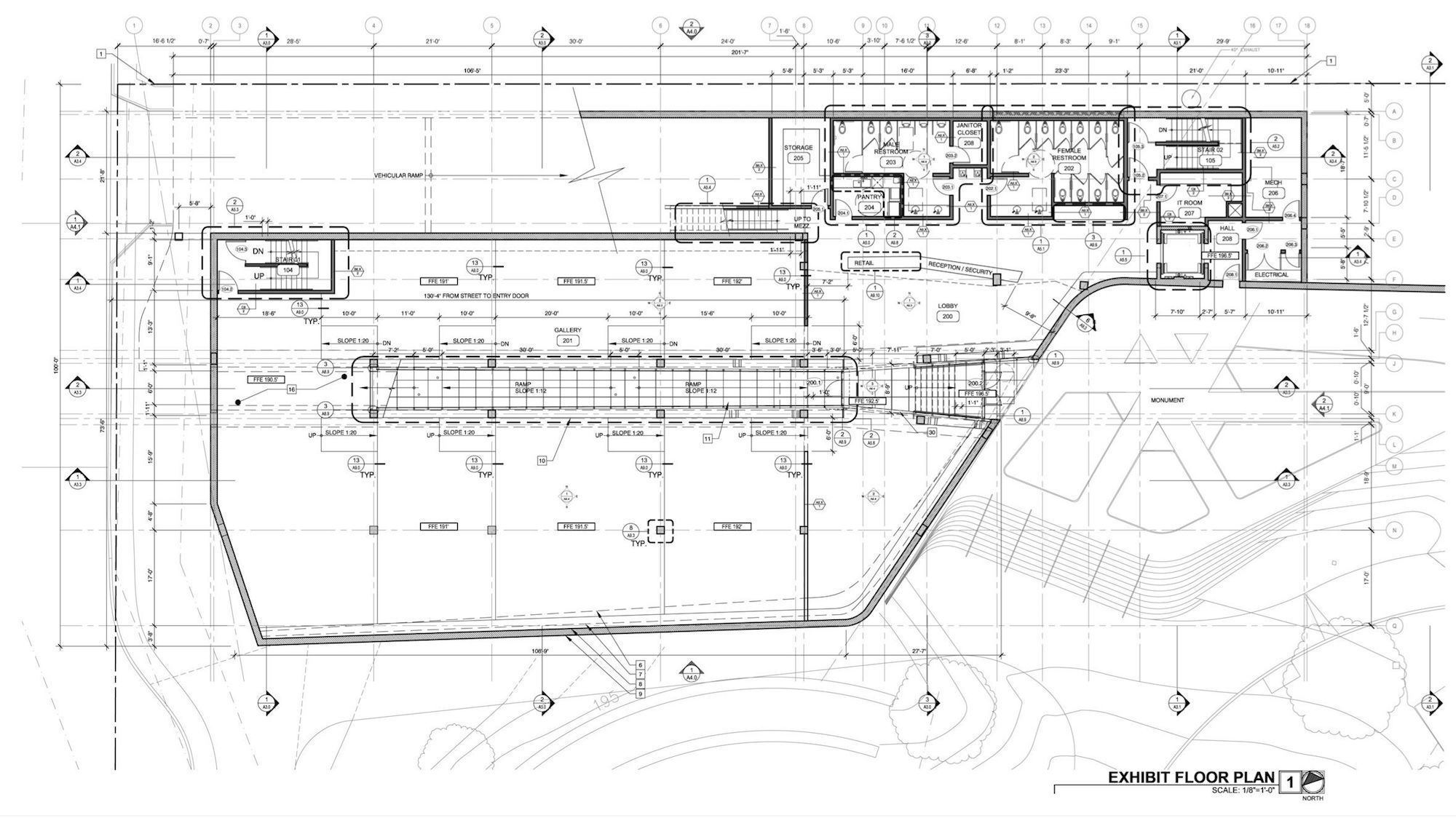

Location: 100 South The Grove Drive Los Angeles, California, USA

Year: 2010

Size: 27,000 sqft

Description:

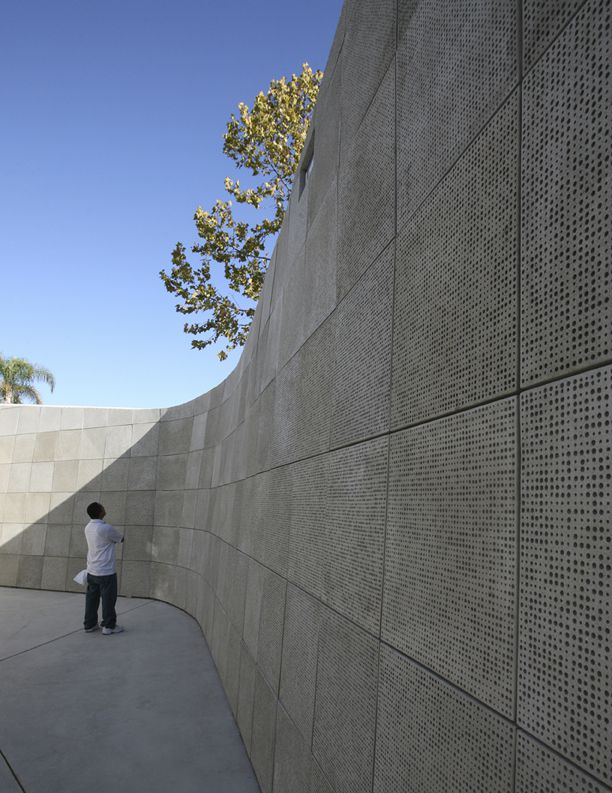

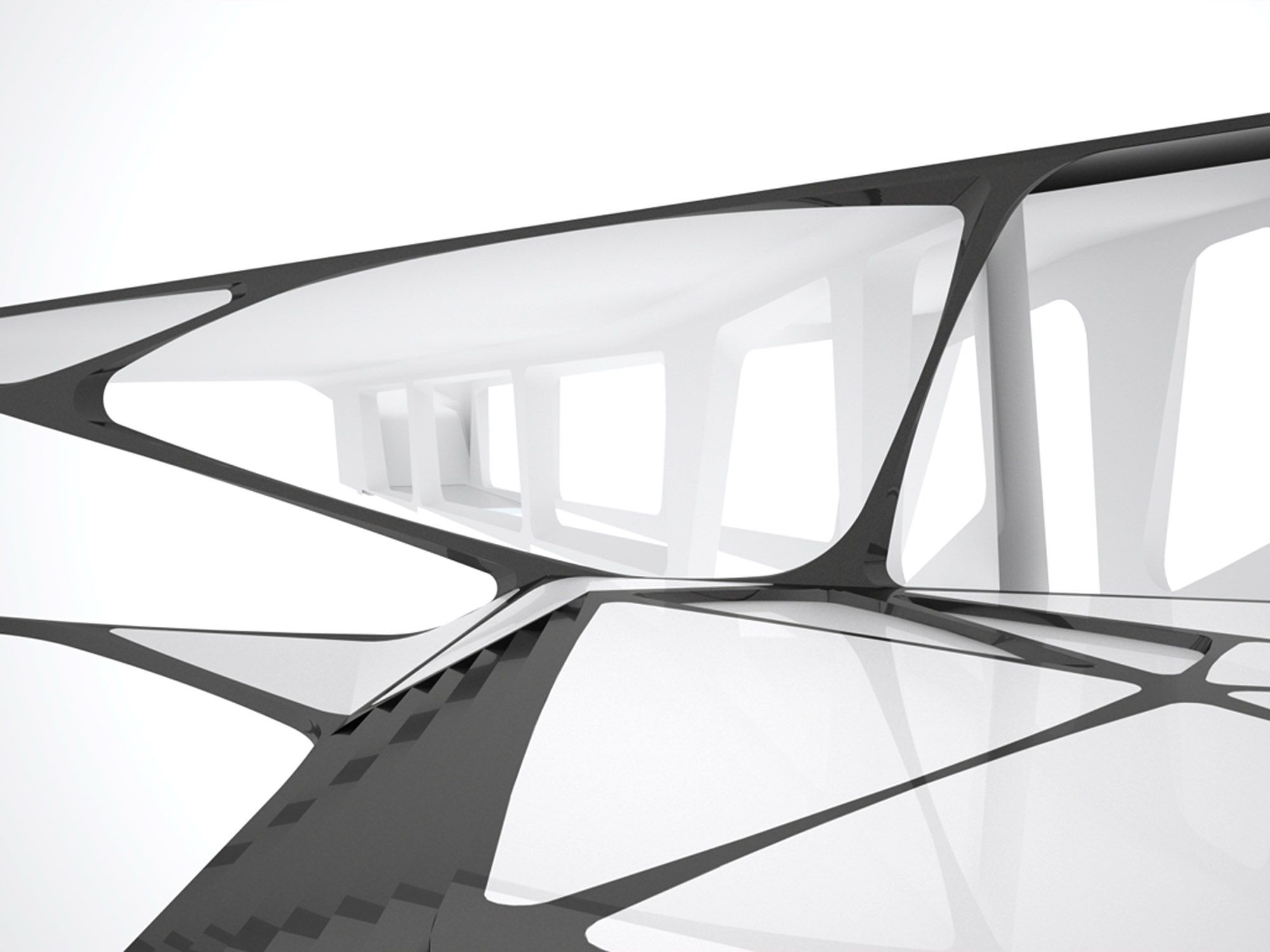

The Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust (LAMH) opened its doors In November of 2010 as the permanent home and display of a collection of artifacts from a ghastly era one-half century passed. Located within a public park at the site of an existing Holocaust memorial, the architecture of the L.A. Museum of the Holocaust straddles the line between autonomous sculpture and a civic destination mindful of the institution and public audience it serves. Photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Museums must function in a precise manner to simultaneously deliver a message through potent content presentation while offering a spatial experience which affords visitors a contemplative asylum. Additionally, this museum uses architecture to enhance the ambient foundation for visitors to receive the intended messages being delivered through each display. Ultimately, the overall design of the building and interior displays transforms each visitor’s encounter with the building and surrounding park into a memorable event capable of instilling a lasting impression of the genocide which occurred and the tolerance needed to move forward compassionately.

Photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Museums must function in a precise manner to simultaneously deliver a message through potent content presentation while offering a spatial experience which affords visitors a contemplative asylum. Additionally, this museum uses architecture to enhance the ambient foundation for visitors to receive the intended messages being delivered through each display. Ultimately, the overall design of the building and interior displays transforms each visitor’s encounter with the building and surrounding park into a memorable event capable of instilling a lasting impression of the genocide which occurred and the tolerance needed to move forward compassionately.

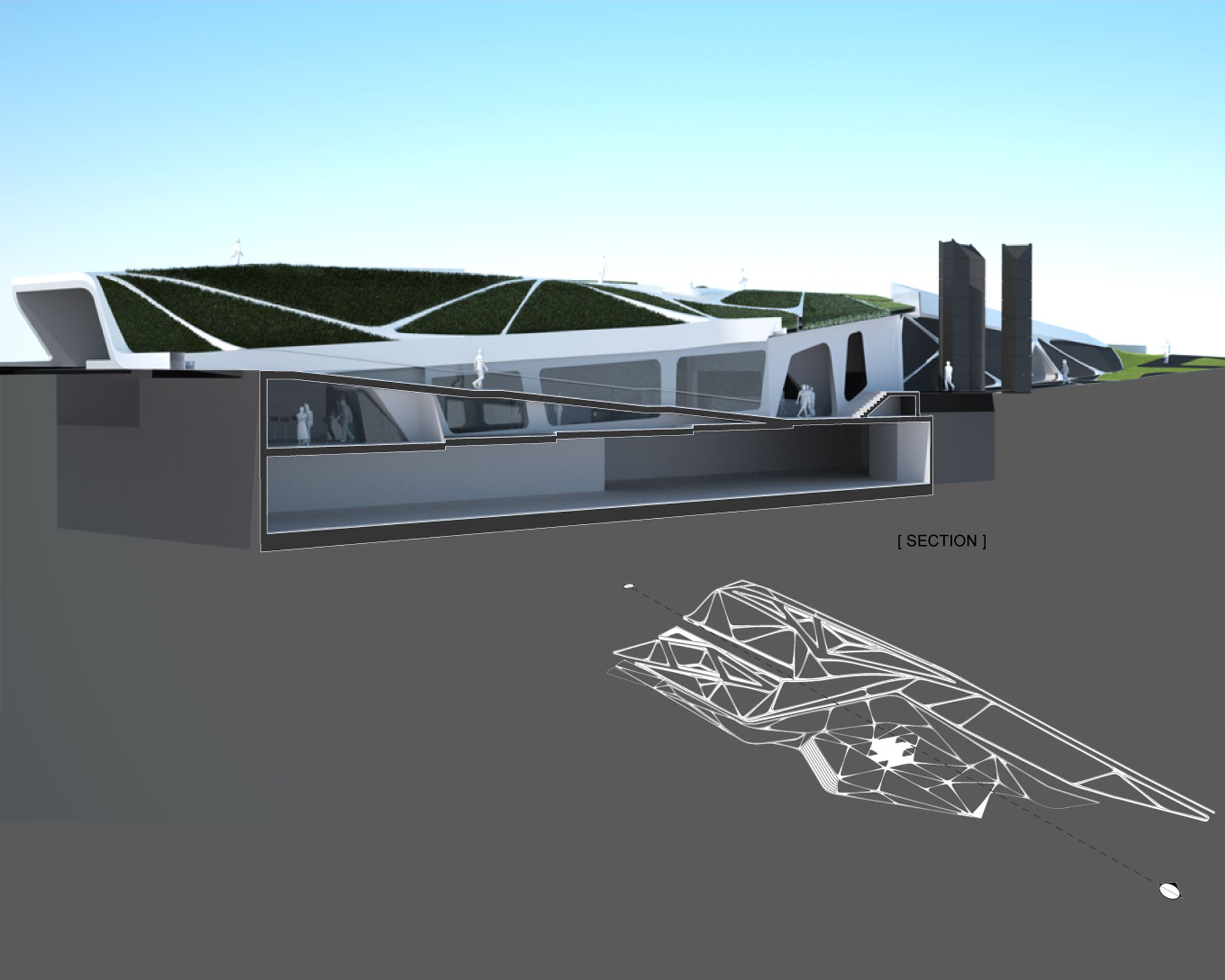

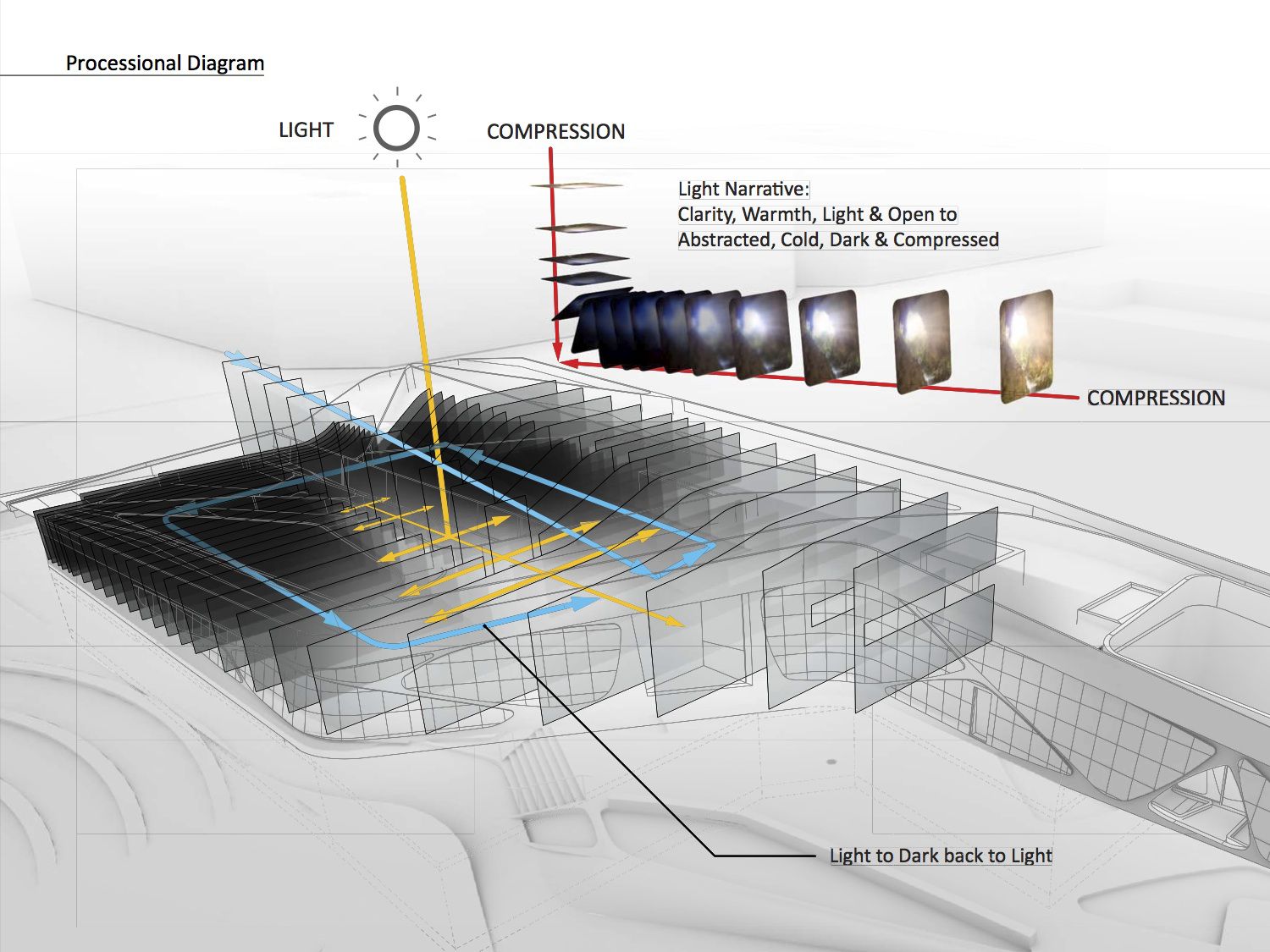

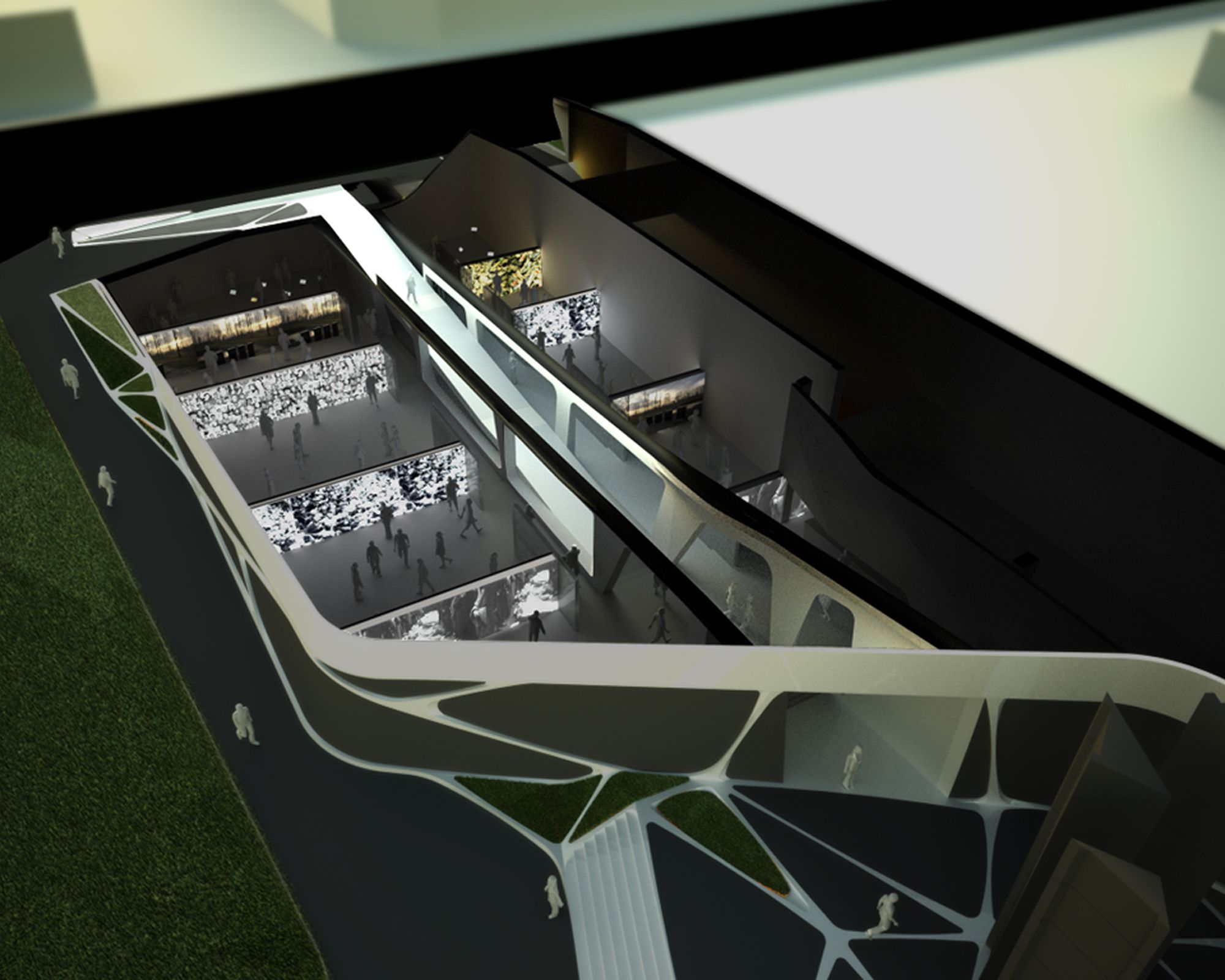

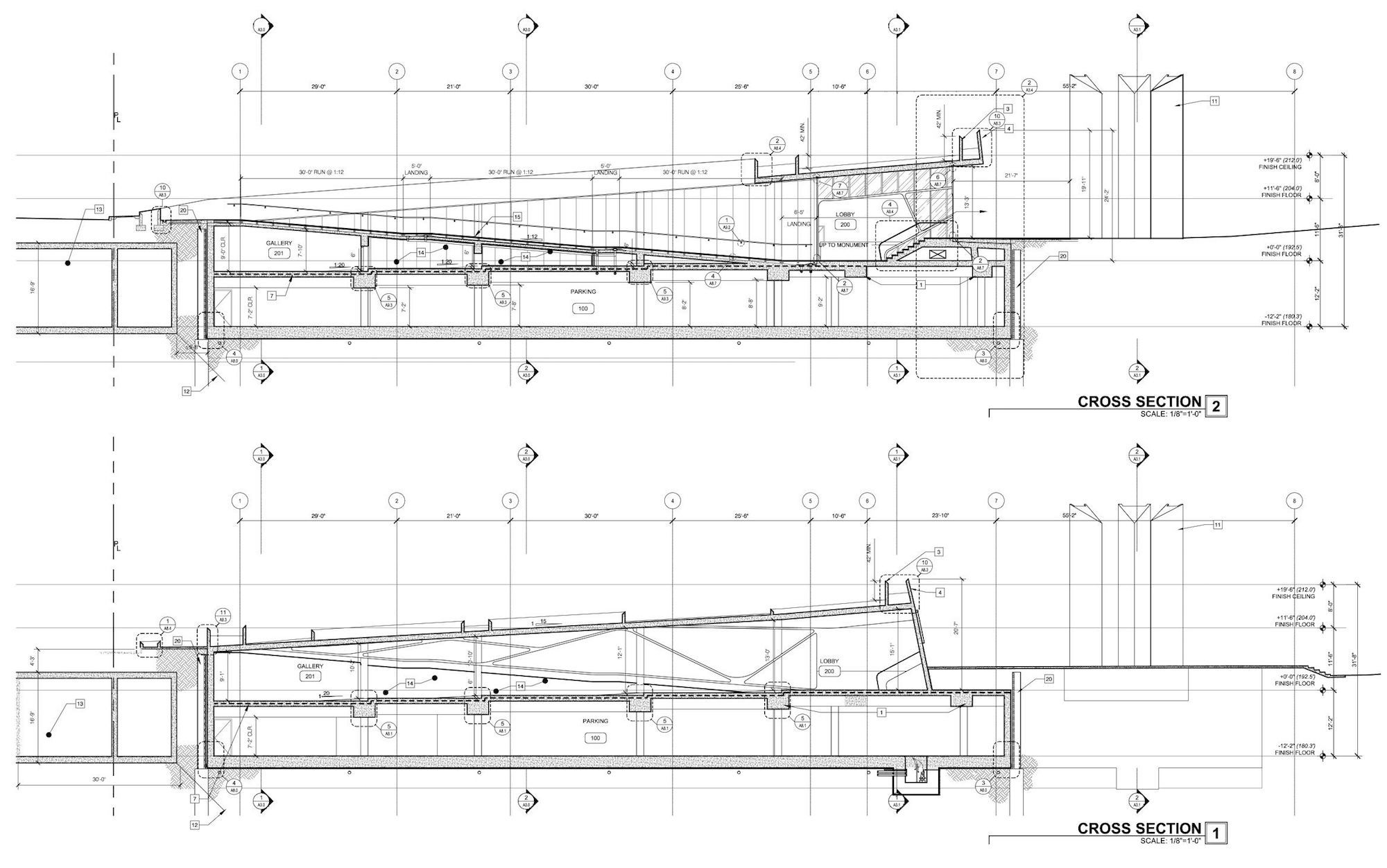

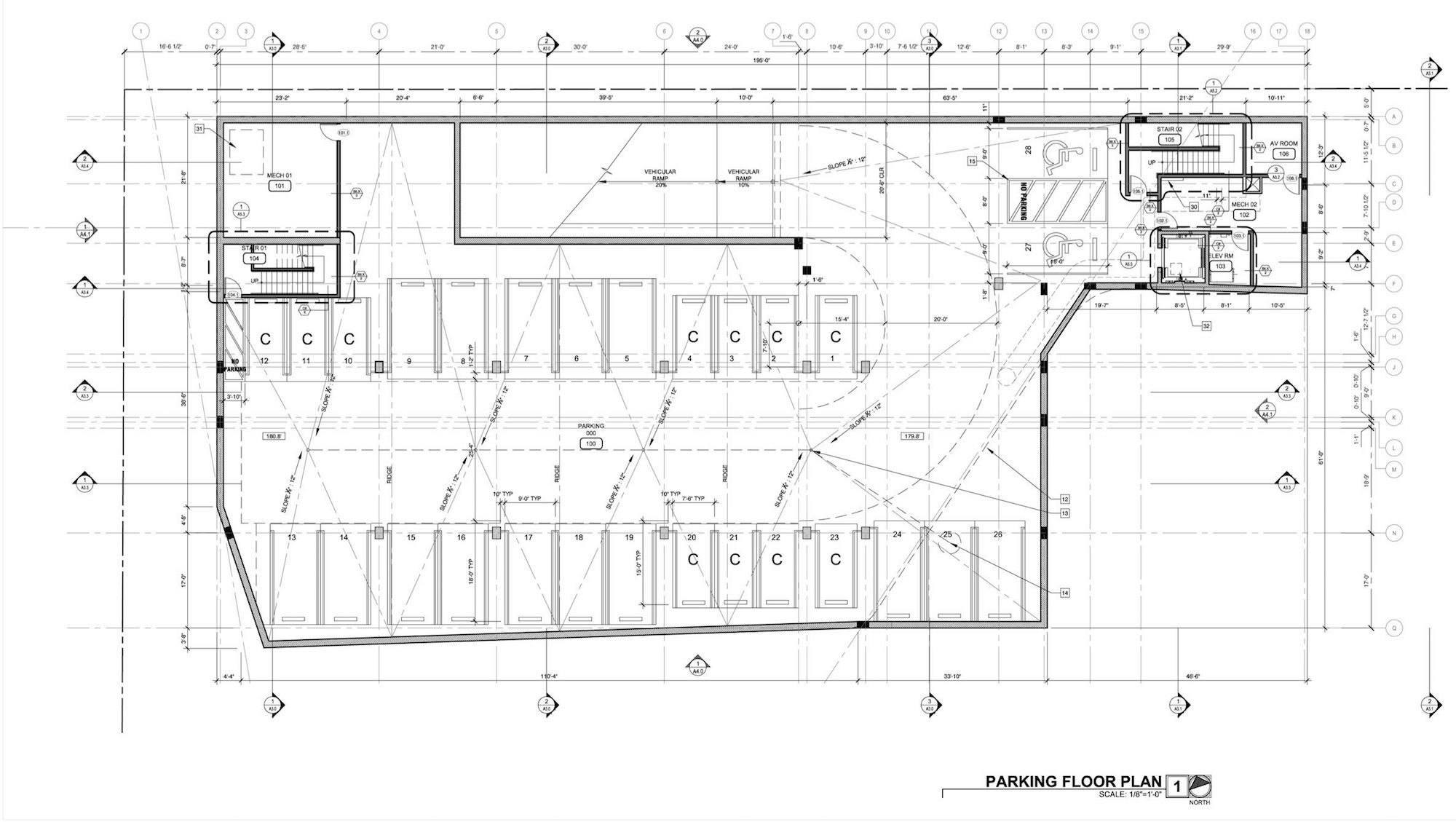

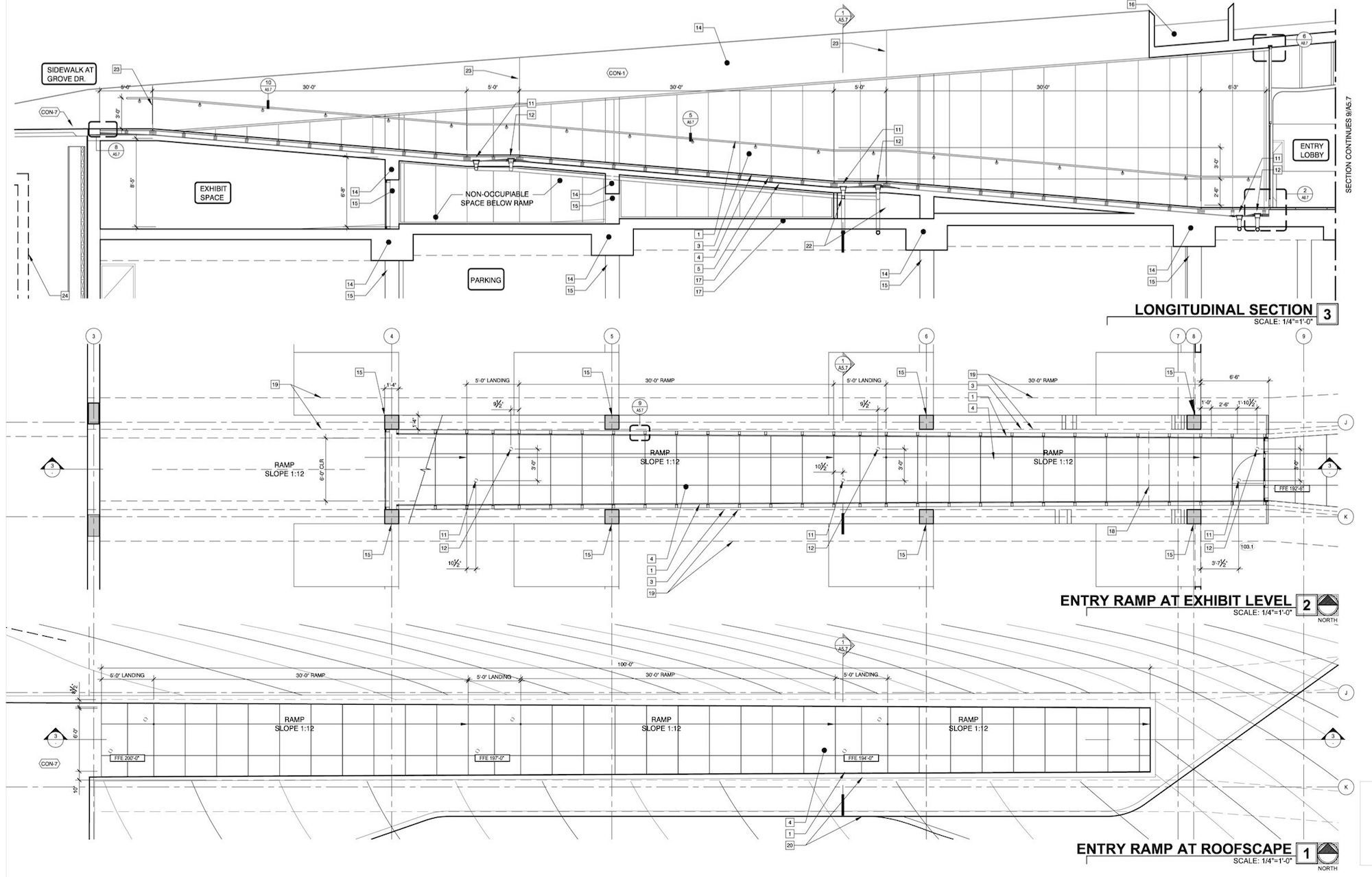

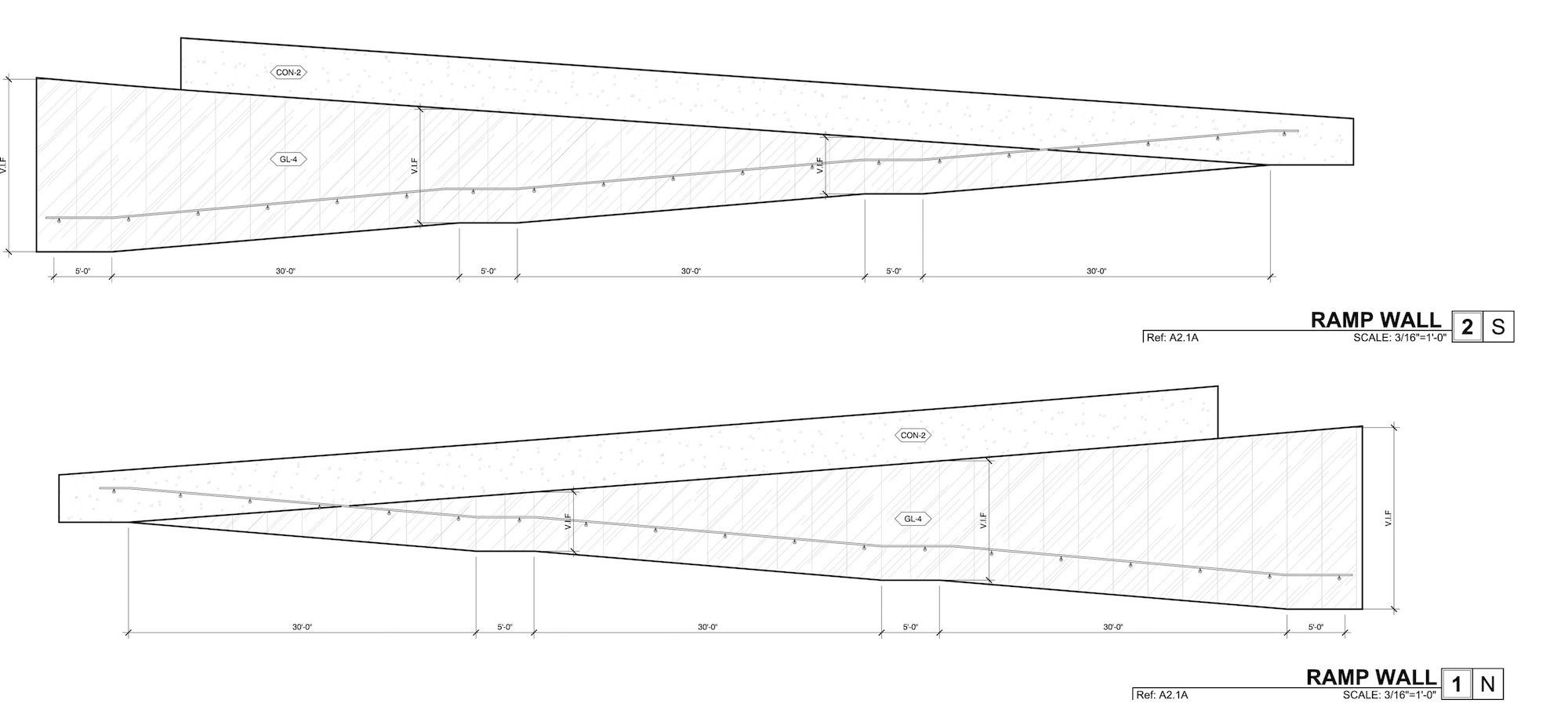

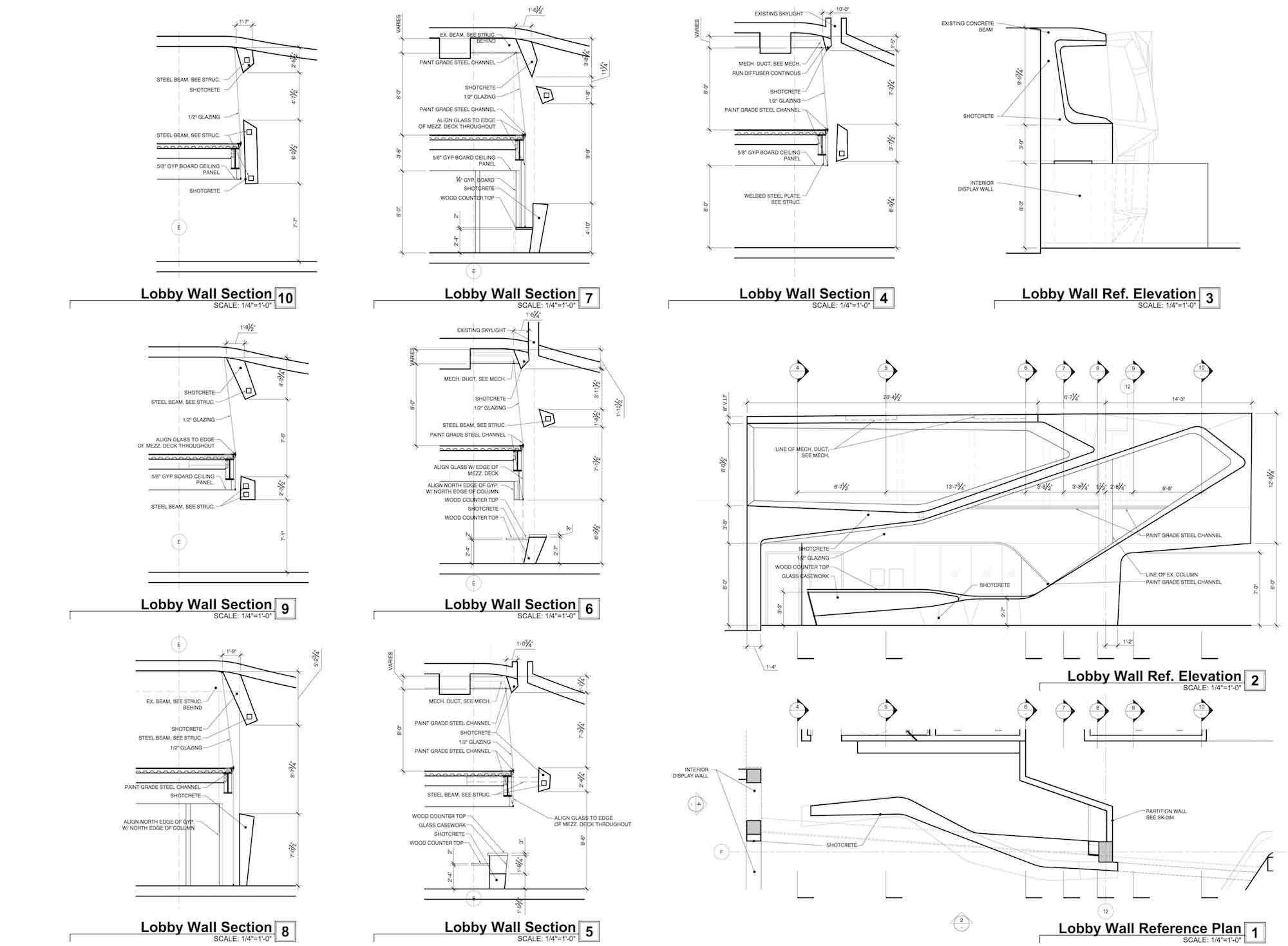

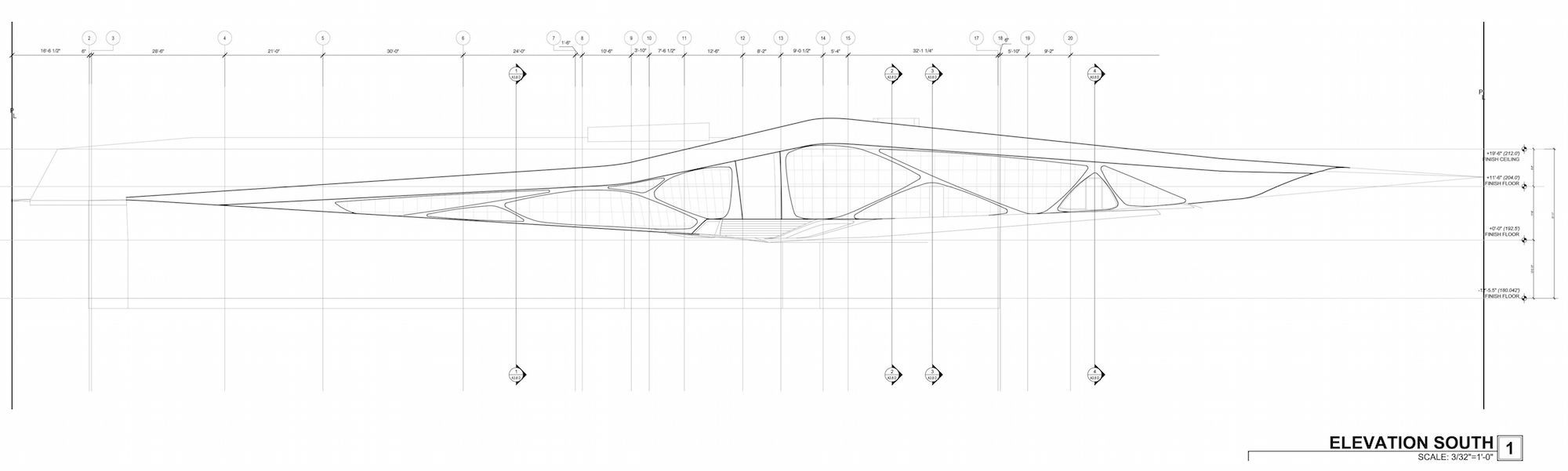

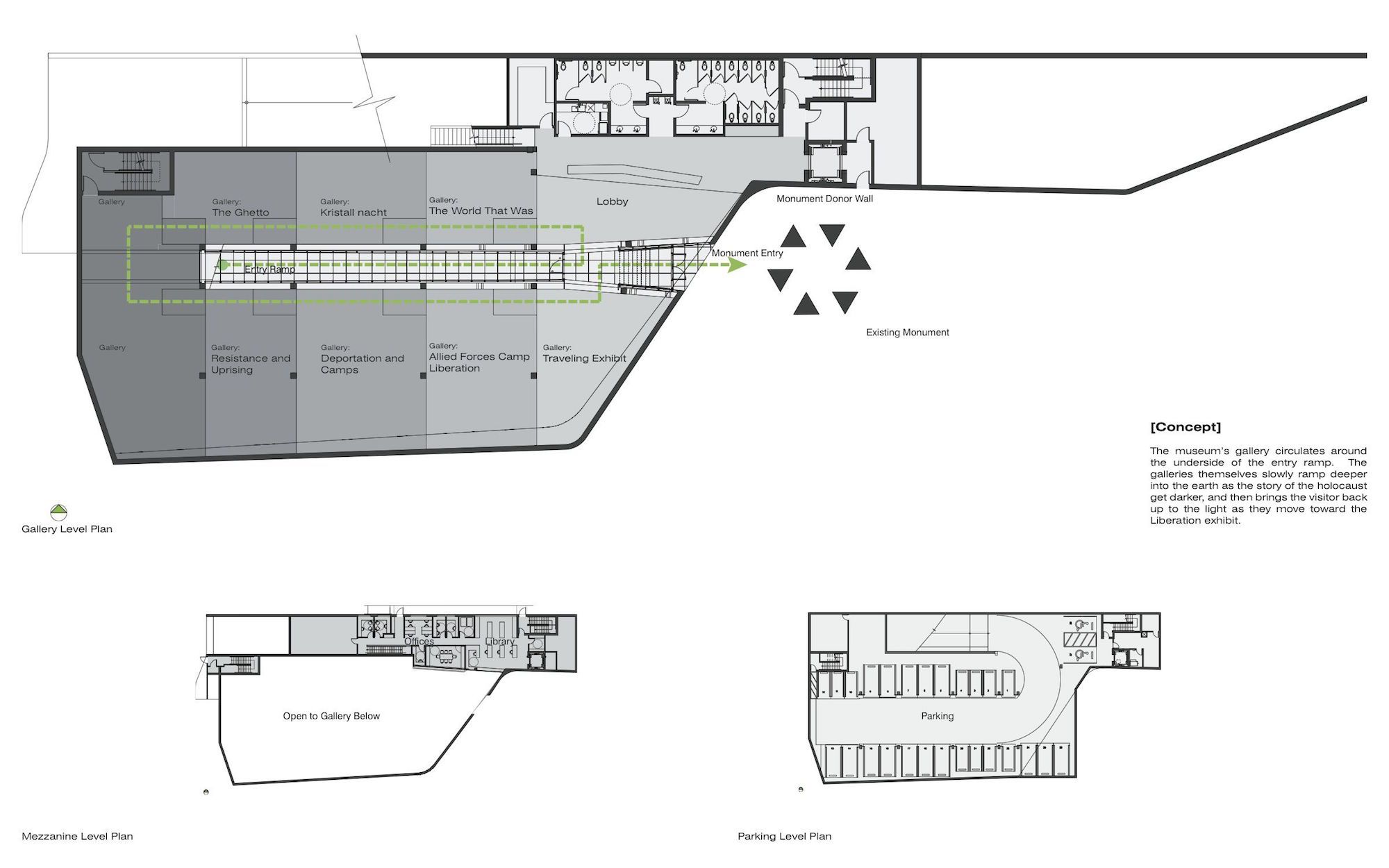

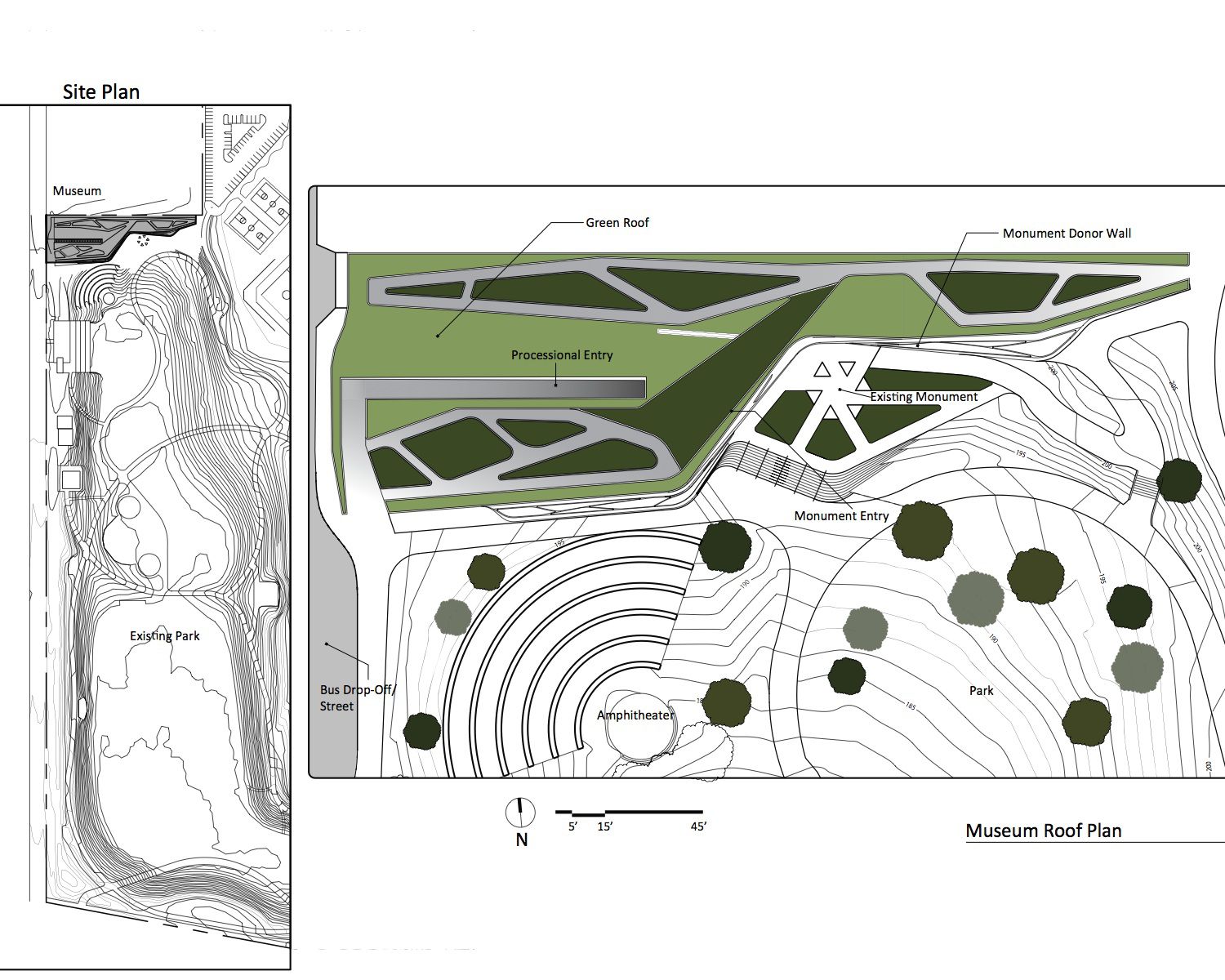

The design intent is to allegorically relate the visitor’s chronological experience of the building to that of Holocaust victims. In order to achieve this, the experience of the building is largely dictated by the timeline of a visitor’s passage from point of arrival through to his/her ascension back to park level from the underground exhibit spaces. Students and patrons begin their procession at the drop off adjacent to the park. Their approach is pervaded by sounds and sights of laughter and sport—of kids playing in the park and picnicking with their families. Because the building is partially submerged beneath the grassy, park landscape, entry to the building entails a gradual deterioration of this visual and auditory connection to the park while descending a long ramp. Attention is shifted toward the existing monument with a narrow view of the towering, black stone pillars sliced horizontally by the ground plane created by the museum’s roof. Upon entering, visitors experience the culmination of their transition from a playful and unrestrained, public park atmosphere to a serious and isolated space saturated with abhorrent imagery. As part of the design strategy, this dichotomous relationship between building content and site context was emphasized to bolster the experience inside the museum and correlate the proximity with which German forest revelers enjoying public parks were to sites of horrific and inhumane acts being carried out in 1930’s and 40’s. Additionally, visitors exit the museum by ascending up to the level of the existing monument, regaining the visual and auditory connection with the park atmosphere and consummating the museum experience with a feeling of resolve—implanting a lasting impression of remembrance for each visitor to take home.

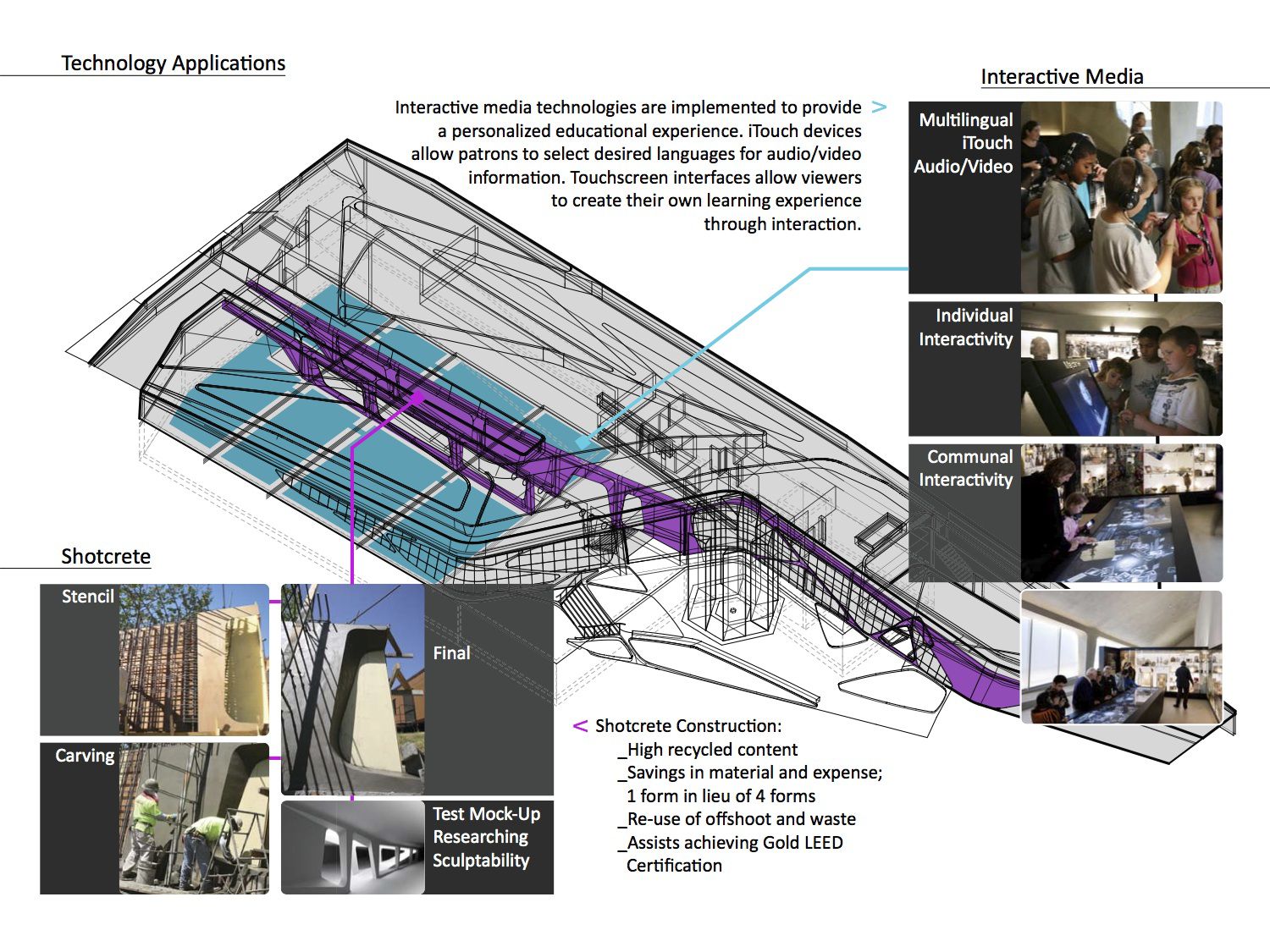

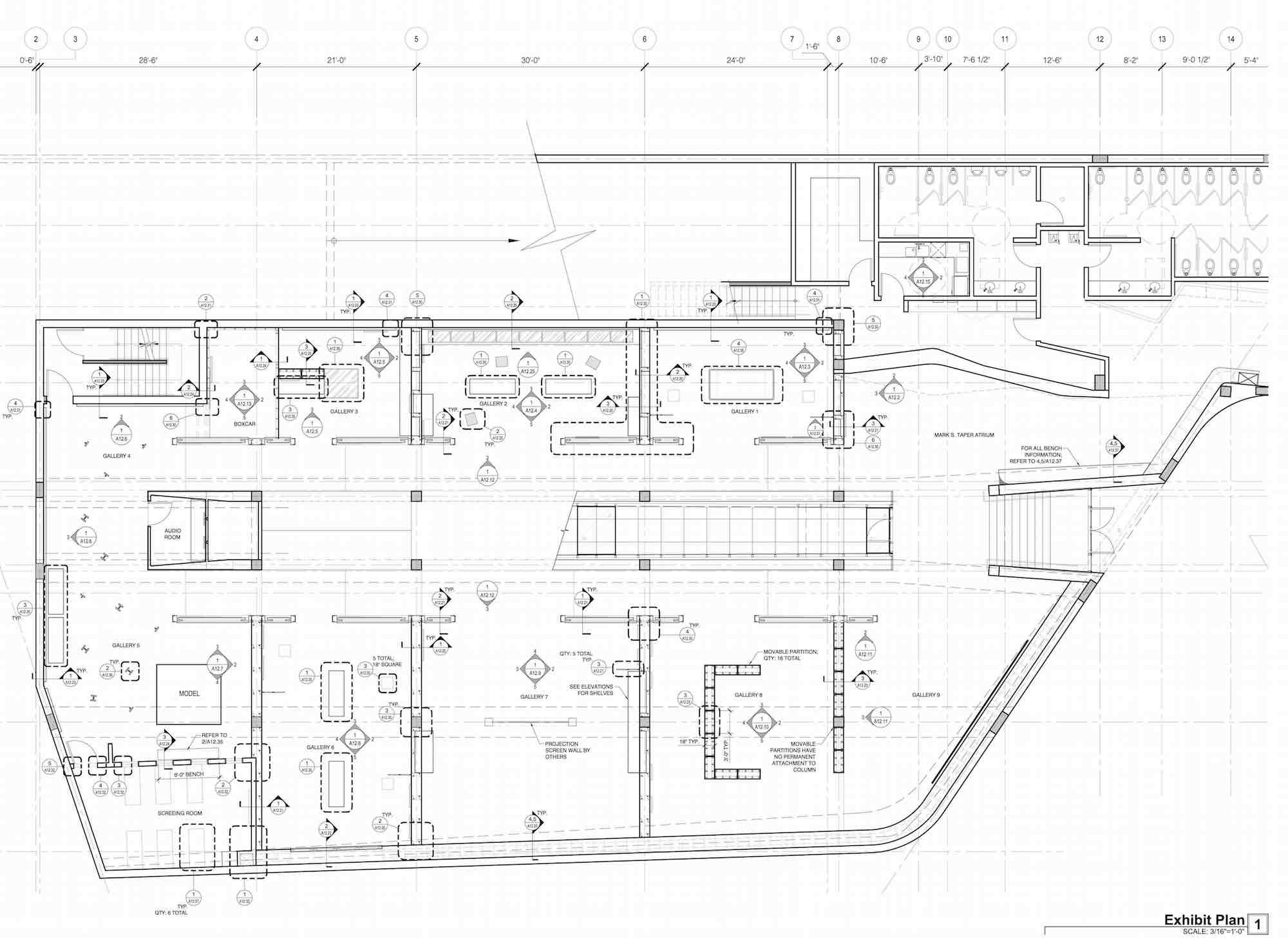

The curatorial ensemble of exhibits, displays and interactive components highlight the museum’s effort to avoid the daunting nature of information depositories by enlivening the content through interactive elements and orchestrating the succession of exhibitions and galleries in a manner which truly supports a cohesive museum experience. Due to the breadth of history and vast volume of historical records in hand, the museum, through its architectural design as an allegorical interpretation of the Holocaust era, provides a first-hand ‘sensory experience’ to each visitor to bolster his/her capacity to associate feelings with the graphic content—inducing a personal connection more susceptible to being learned and remembered. The first room is titled, “The World That Was” and incorporates a large, single interactive table mimicking the social comfort of pre-war communities by bringing all visitors together. The lighting of the interior space dims as the visitor steps down into the subsequent room where two separate exhibits depicting “Kristallnacht” and a “Book Burning” display divide the singular crowd—diminishing the warmth provided by people close-by. Through the third room and into the fourth, the floor continues to step down as ambient lighting becomes scarcer leading individuals to the room titled, “Concentration Camps.” The ceiling is low, and the room is almost entirely illuminated by numerous, video-monitors—about the size of a notebook—which limits viewing to a single spectator. The visitor is now learning about one of the darkest moments in human history while confined to the most isolated, underground area in the museum. The journey from this point forward is one of ascension and of finding the comfort of familiar space as floor levels begin to rise and natural lights begins to penetrate the interior once again. The final ascent up to the existing monument is liberating—filled with sights of unrestricted park land, the warmth of California sun on one’s skin, and of rejuvenating breaths of fresh air as the visitor distances him/herself from the museum. It is this process of mutual learning and experiencing which secures the message of the museum into the minds and hearts of each visitor far beyond the walls of the building and the sidewalks lining the park. In fact, the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust is interconnected with the museum and learning center, Yad Vashem, in Jerusalem through a shared database of digital content which expands the spectrum of material available to the museum to keep content new, interesting and worthy of repeat visits. By formatting information in an engaging, holistic manner, promoting an ideal of tolerance to our youth becomes achievable and impactful.

The Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust shows how buildings can perform. It provides a necessary backdrop and environment to assist daily functions, heighten spatial experience and, in the case of this museum, reinforce the message of the content being delivered. The aesthetic appeal and spirited integration with the park alone may offer visitors reason enough to attend, but the inherent symbolism of the design shakes up one’s stereotype of museums, and opens one’s mind to the realm of human possibility—be it the devastating potential evidenced in past crimes against humanity or the inspiring capacity of creators and builders to conceive and manifest a wonderment of novel construction.

Contextual Strategy:

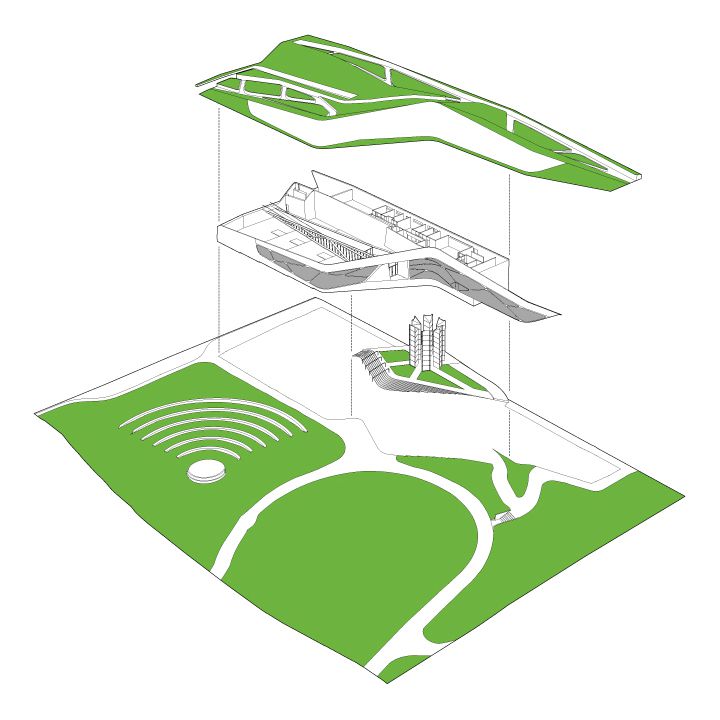

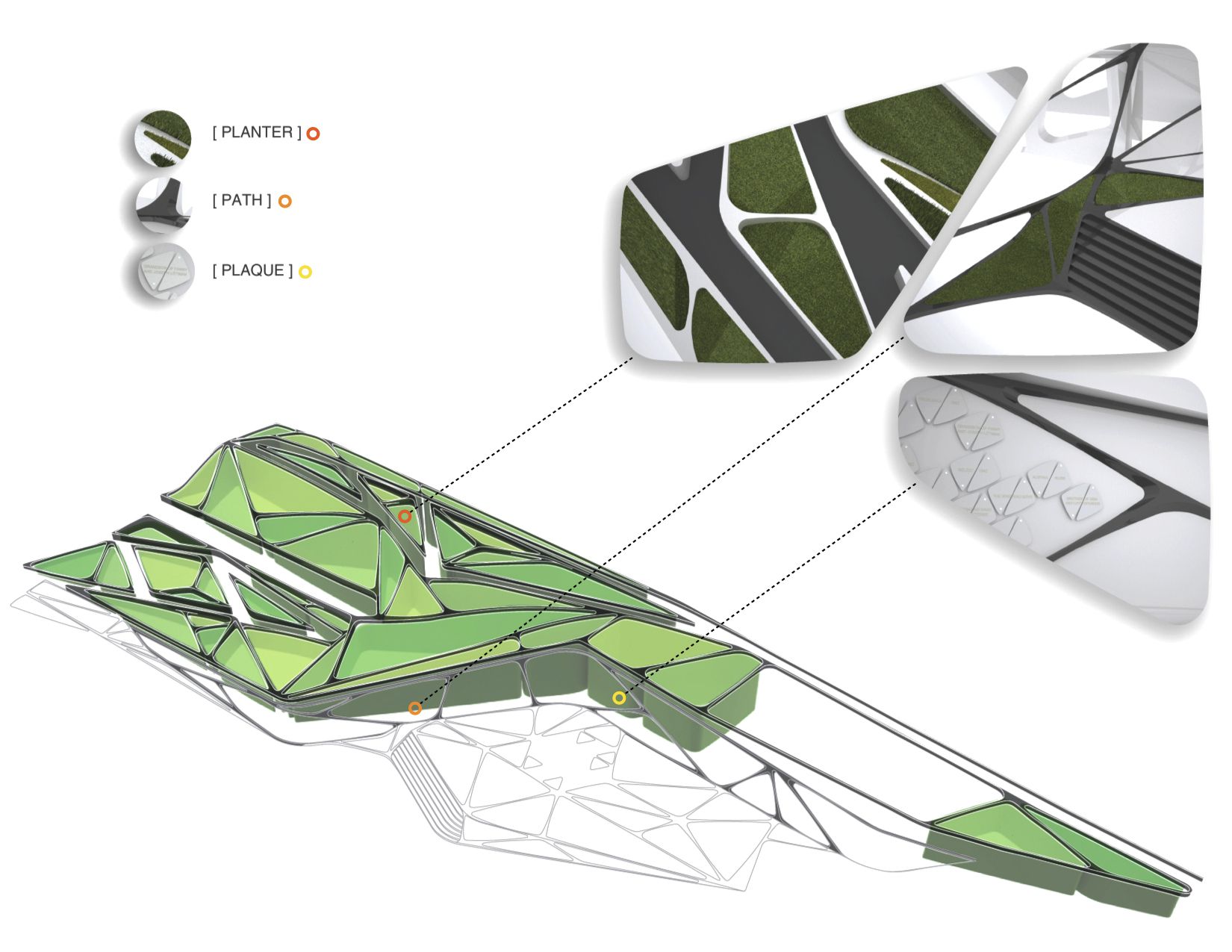

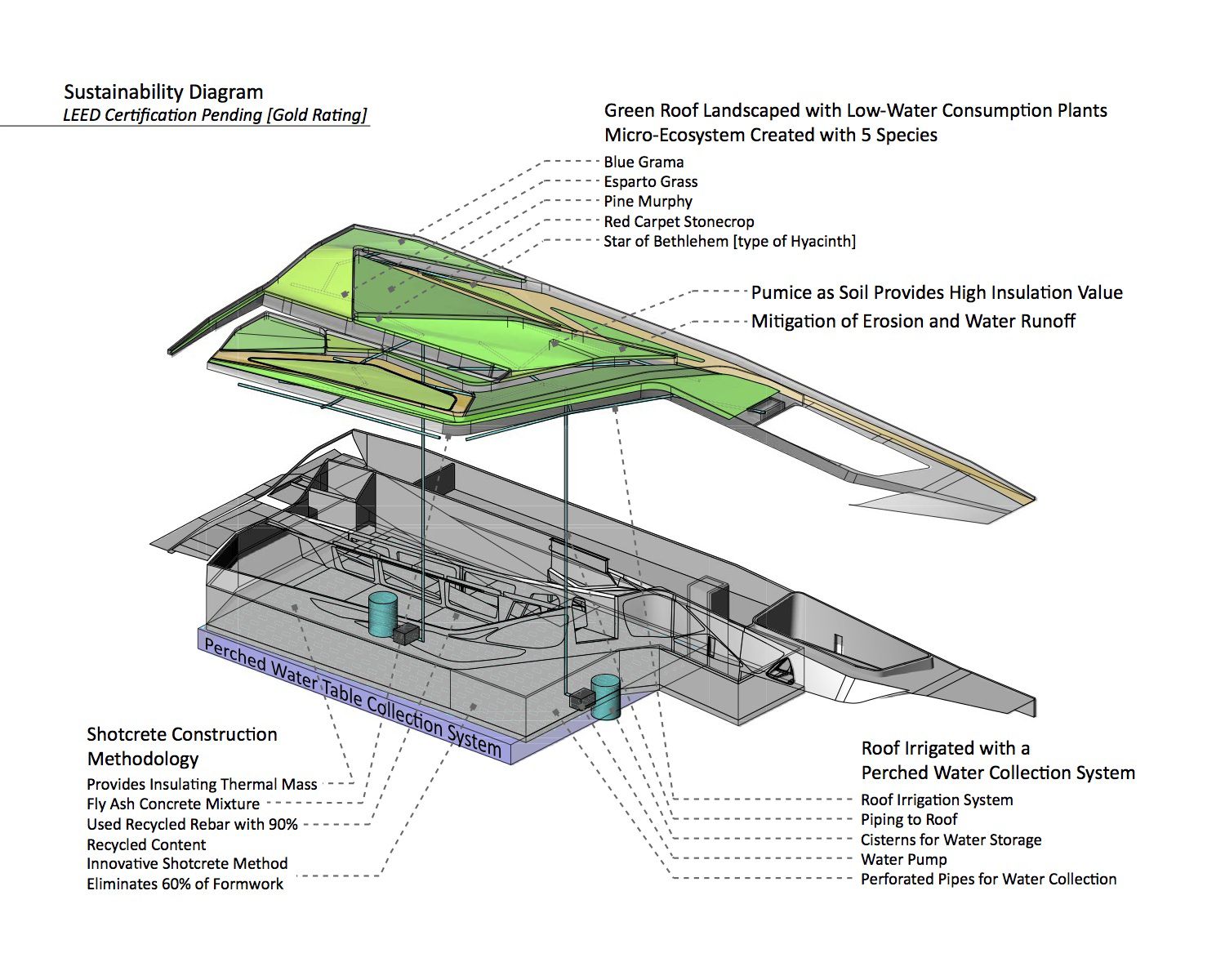

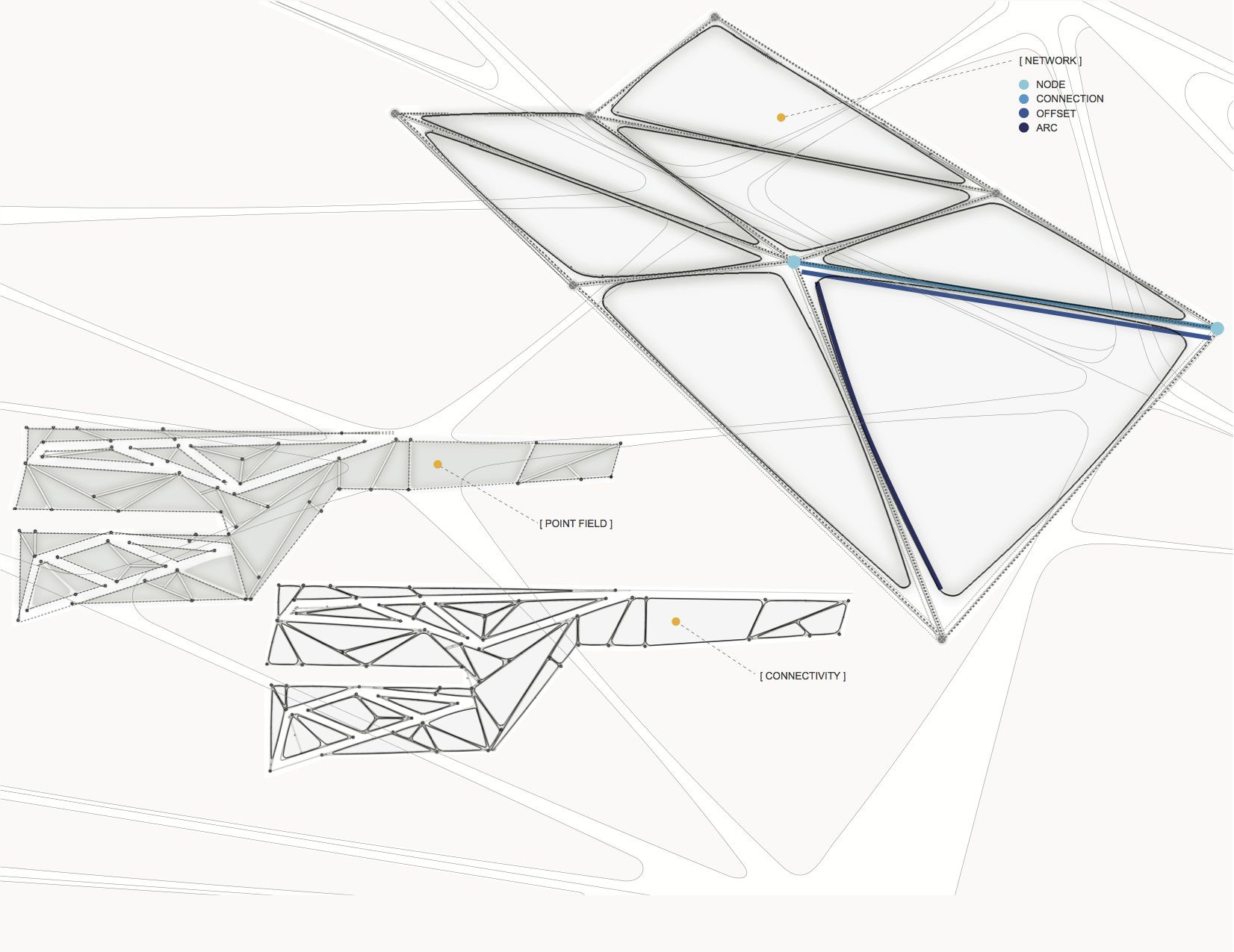

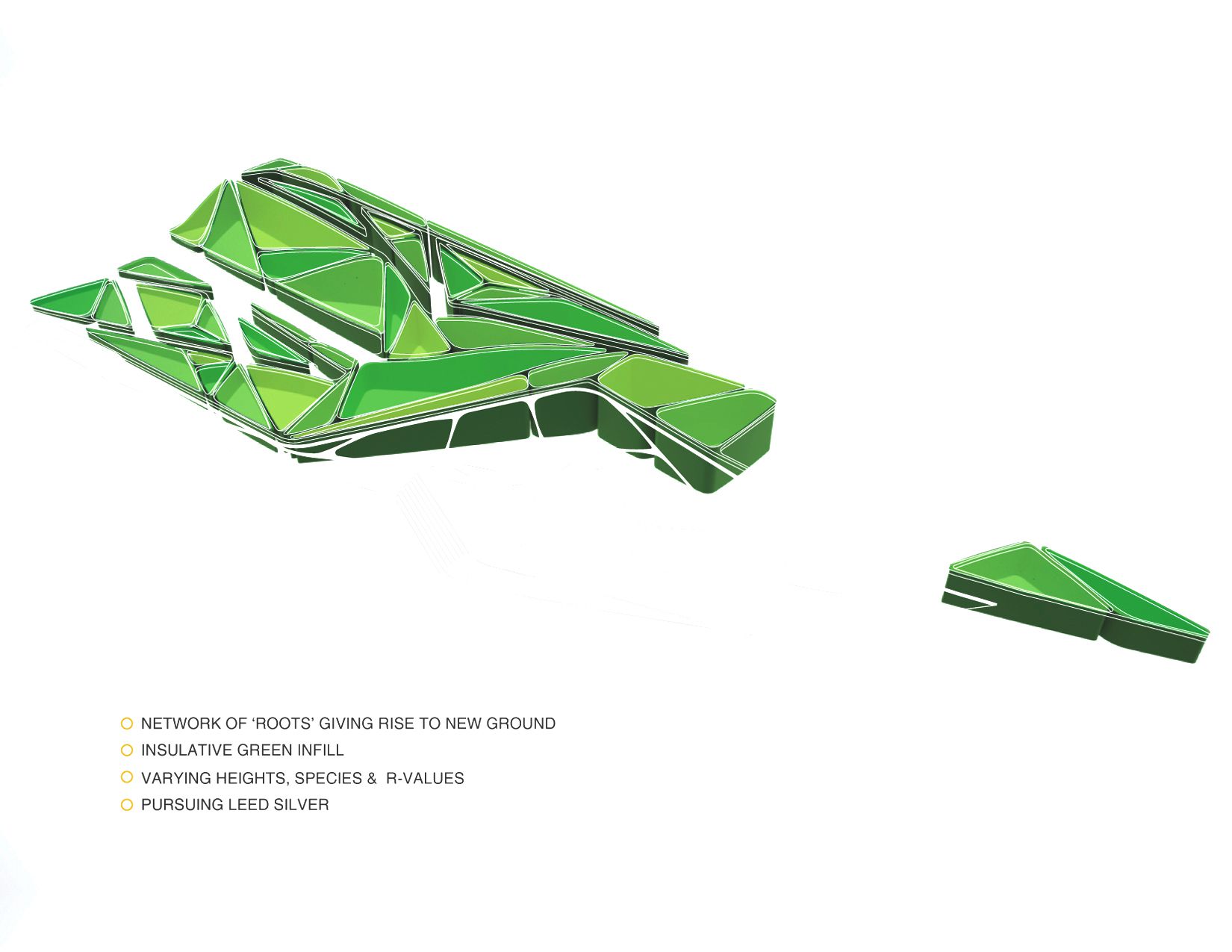

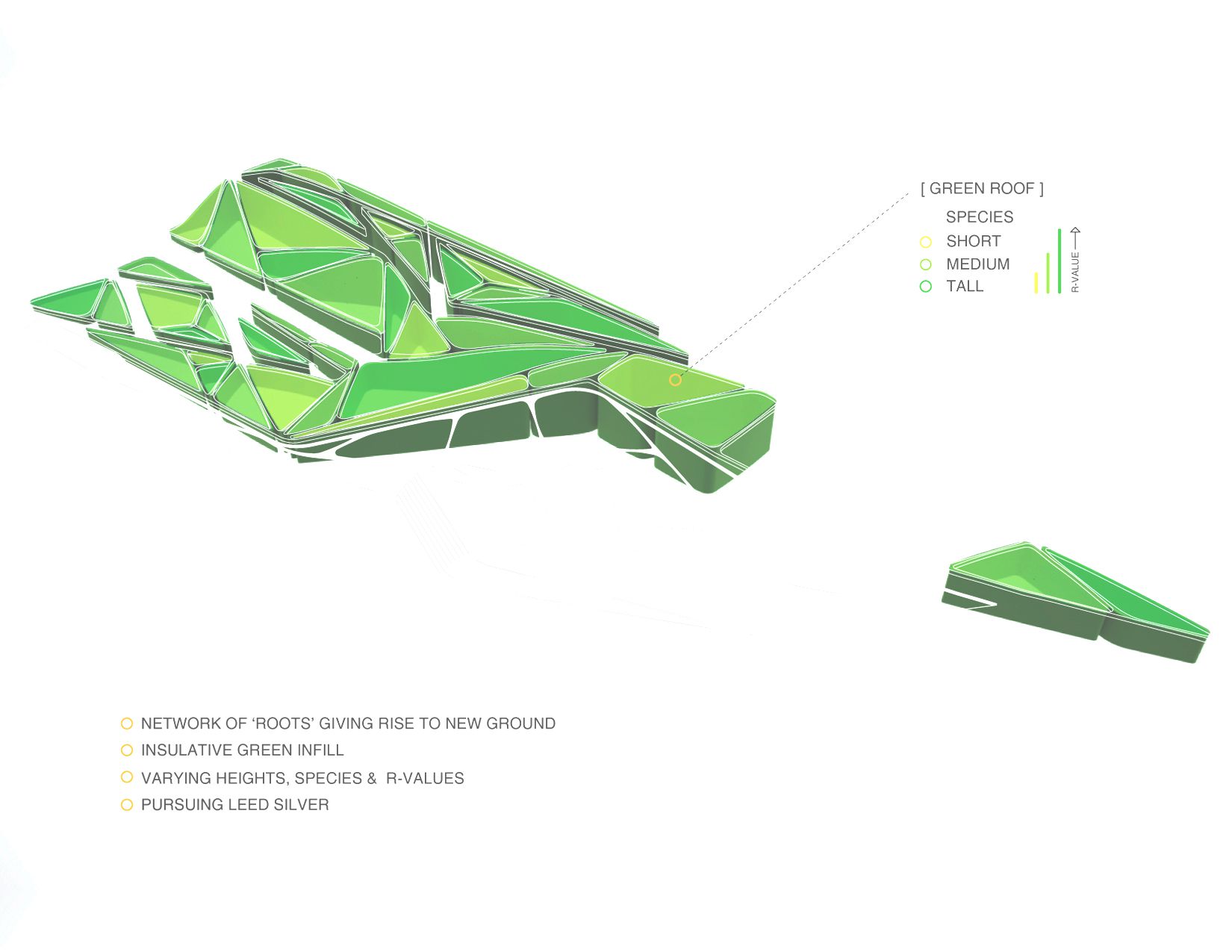

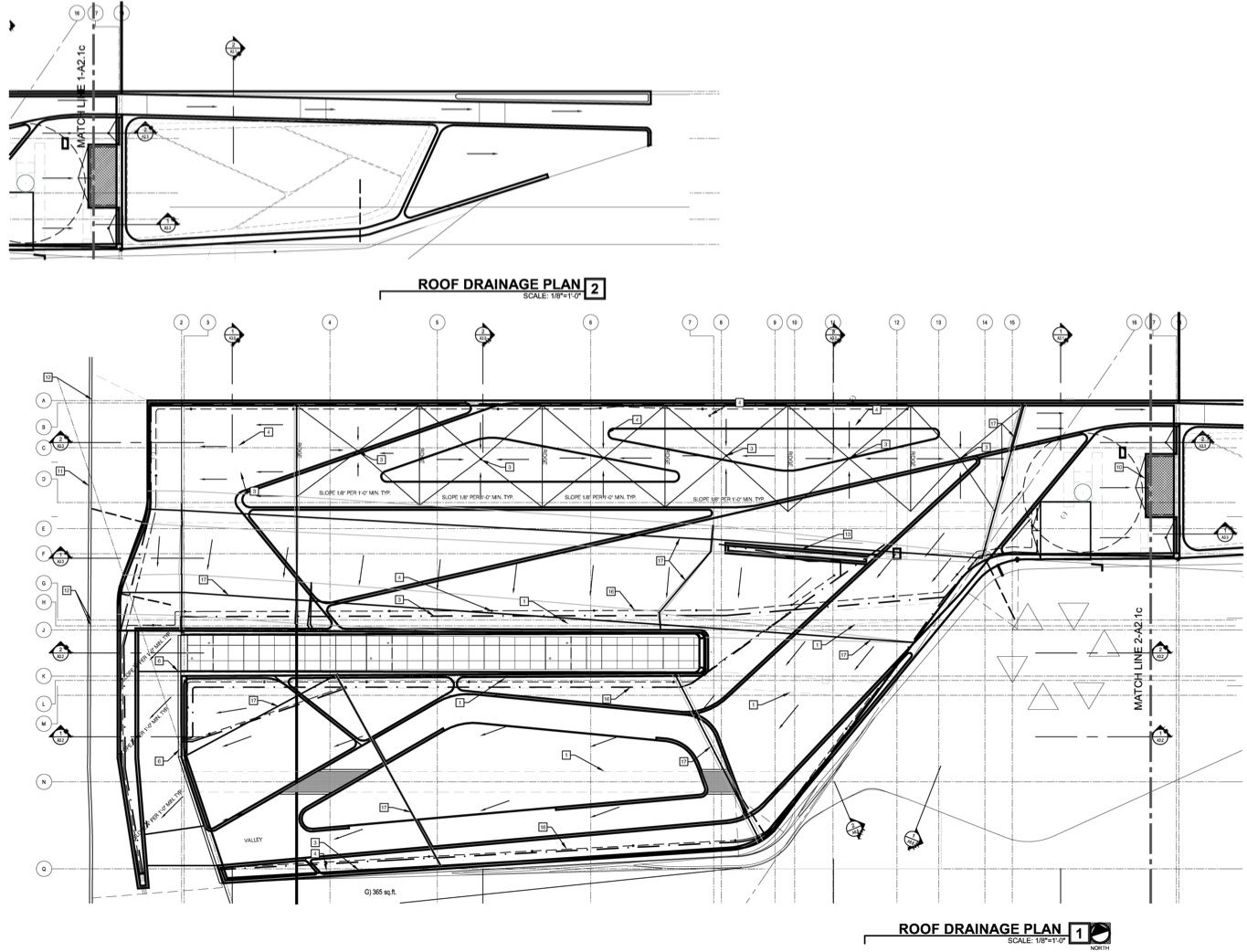

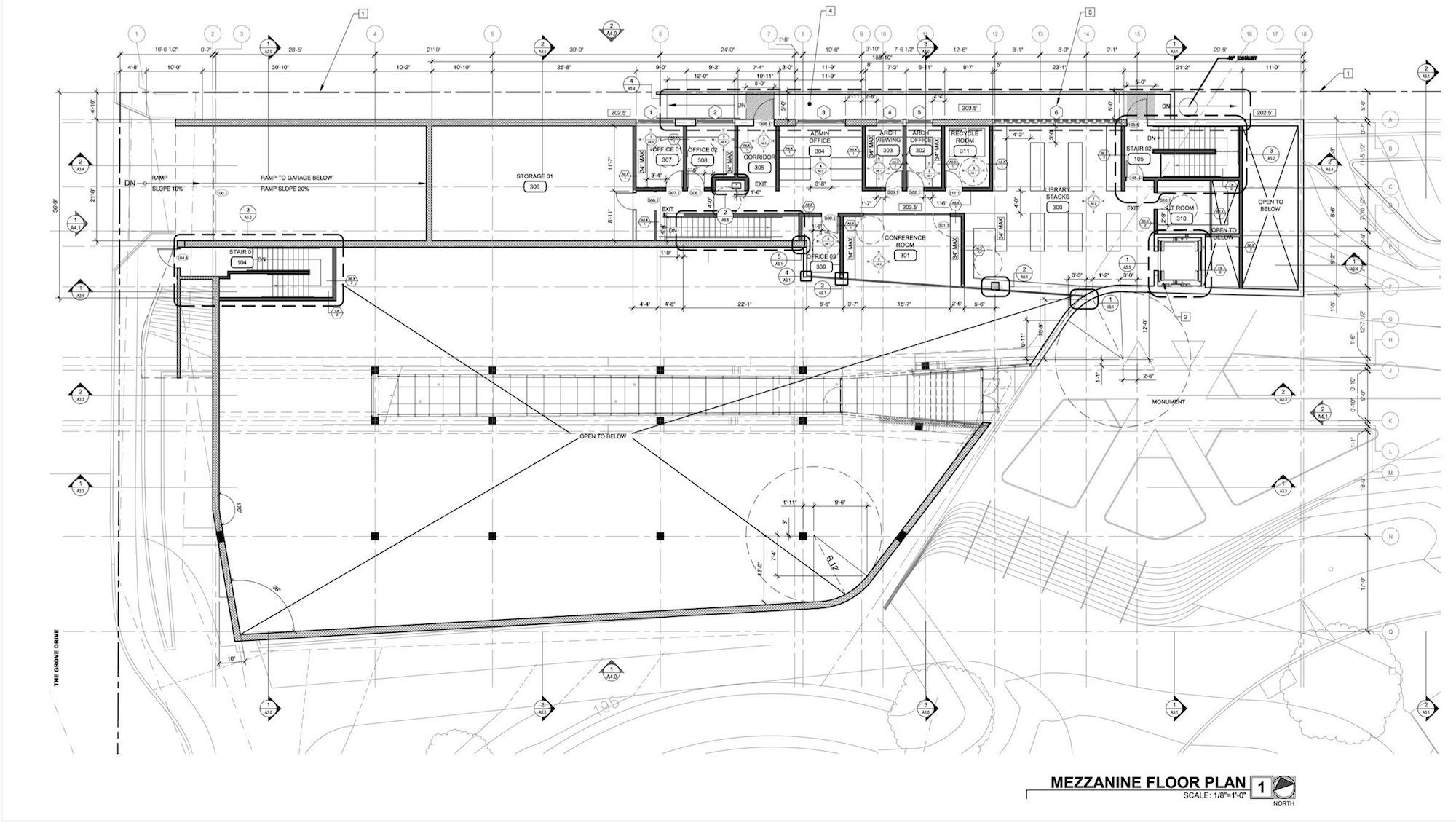

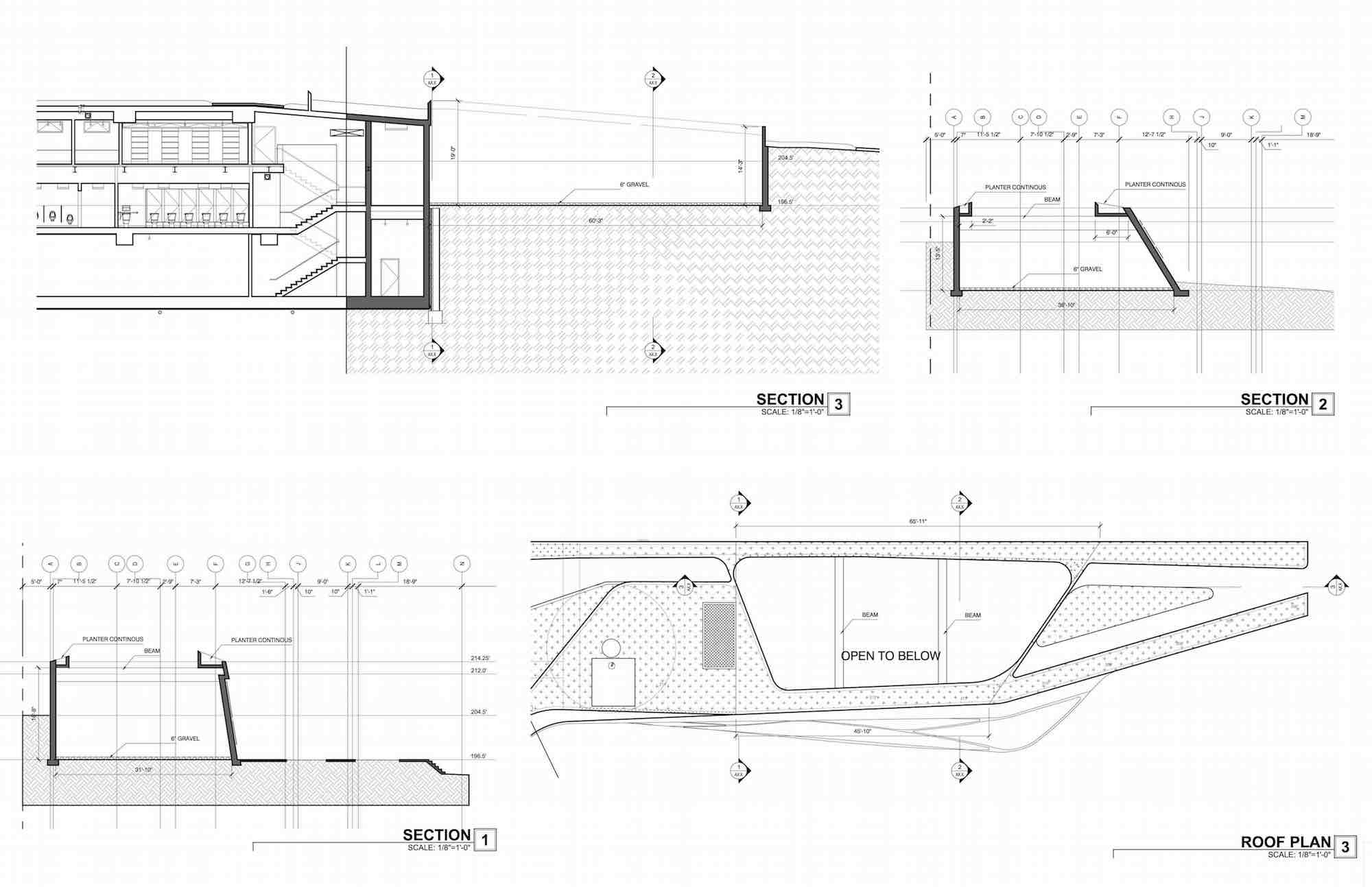

The new building for the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust (LAMH) is located within a public park, adjacent to the existing Los Angeles Holocaust Memorial. Paramount to the design strategy is the integration of the building into the surrounding open, park landscape. The museum is submerged into the ground allowing the park’s landscape to continue over the roof of the structure. Existing park pathways are used as connective elements to integrate the pedestrian flow of the park with the new circulation for museum visitors. The pathways are morphed onto the building and appropriated as surface patterning. The patterning continues above the museum’s galleries, further connecting the park’s landscape and pedestrian paths. By maintaining the material pallet of the park and extending it onto the museum, the hues and textures of concrete and vegetation blend with the existing material palette of Pan Pacific Park. These simple moves create a distinctive façade for the museum while maintaining the parks topography and landscape. The museum emerges from the landscape as a single, curving concrete wall that splits and carves into the ground to form the entry. Designed and constructed with sustainable systems and materials, the LAMOTH building is on track to receive a LEED Gold Certification from the US Green Building Council.

Circulatory Strategy:

Patrons begin their procession at the drop off adjacent to the park. Their approach is pervaded by sounds and sights of laughter and sport—of kids playing in the park and picnicking with their families. Because the building is partially submerged beneath the grassy, park landscape, entry to the building entails a gradual deterioration of this visual and auditory connection to the park while descending a long ramp. Upon entering, visitors experience the culmination of their transition from a playful and unrestrained, public park atmosphere to a series of isolated spaces saturated with photographic archival imagery. As part of the design strategy, this dichotomous relationship between building content and landscape context is emphasized to bolster the experience inside the museum and allegorically correlate the proximity with which German forest revelers enjoying public parks were to sites of horrific and inhumane acts being carried out in 1930’s and 40’s. Visitors exit the museum by ascending up to the level of the existing monument, regaining the visual and auditory connection with the park environs.

The first room is titled, “The World That Was”, and incorporates a large, single interactive table, mimicking a conceptual “community” or dinner table. The exhibit brings a large group of patrons together around one interactive exhibit. The lighting of the interior galleries dim as the visitor steps down into the subsequent rooms where two separate exhibits depicting “Kristallnacht” and a “Book Burning” display divide the singular crowd—diminishing the “community” provided by people nearby. Through the third room and into the fourth, the floor continues to step down as ambient lighting becomes scarcer leading individuals to the room titled, “Concentration Camps.” The ceiling is low, and the room is almost entirely illuminated by individual video-monitors—about the size of a notebook—which limits viewing to a single spectator. The visitor is now confined to the most isolated, darkest and volumetrically concentrated underground area in the museum. The journey from this point forward is one of ascension and of finding the comfort of familiar space as floor levels begin to rise and natural lights begins to penetrate the interior once again. The final ascent up to the existing monument is filled with sights and sounds of unrestricted park land.

Performance Qualifications

- Site Development: Maximize Open Space: The museum has been developed in an area with zoning requirements, but with no requirement for open space, and has provided vegetated open space equal to 47.9% of the project’s site area by implementing a roof with 68.1% of its total area being vegetated. The roof is a 15,000 square foot site integrated semi-intensive green roof. This green roof enhances many of the green building performance elements such as maximizing open space, restoring natural habitat and park land, providing heat island roof reduction and urban run-off quantity and quality reduction. The roof is covered by many different species of native grasses which were selected for their water efficient landscaping properties, and minimal maintenance.

- Water Efficient Landscaping: The installed irrigation systems reduce potable water consumption by 71.7% from a calculated baseline case.

- Water Use Reduction: The Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust has reduced potable water use by 53.8% from a calculated baseline design through the installation of high efficiency toilets, waterless urinals and low-flow faucets.

- Optimize Energy Performance: The museum has achieved an energy cost savings of 21.4% using the Title 24-2005 methodology and has a performance improvement of 29.3% using the ASHRAE 90.1-2004 Appendix G methodology. Some of the measures taken to minimize energy usage include high efficiency light fixtures, daylight and occupancy sensors, high efficiency glazing and skylights, high R-value roof structure through the green-roof, high SEER value mechanical equipment, programmable thermostats and ample natural ventilation and daylight.

- Construction Waste Management: The project has diverted 80.4% of on-site generated construction waste from landfill.

- Recycled Content: 19.5% of the total building materials content, by value, have been manufactured using recycled materials.

- Regional Materials: 64.2% of the total building materials value includes building materials and/or products that have been extracted, harvested or recovered, as well as manufactured within 500 miles of the project site.

- Minimum IAQ Performance: The ventilation system has been designed to meet the minimum requirements of ASHRAE 62.1-2004 using the ventilation rate procedure as well as having increased breathing zone outdoor air ventilation rates to all occupied spaces by 30% above the minimum rates required by ASHRAE Standards 62.1-2004 as determined by EQp1.

- Exterior Lighting: The exterior lighting of the museum and its pathways are primarily lit using innovative off the grid LED Solar light poles, the INOVUS solar had intelligent power management – the LEDs gives you the ability to manage light hours and intensity levels so you can save as much as 75% on energy consumption.

- Interior Lighting: The Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust created a comfortable and healthy working environment. In addition to the healthy air quality standards followed, the museum also made sure to provide over 75% of the spaces with natural daylight and views to the outdoors, allowing individual controllability of the lighting and thermal comfort, and maximizing open space for breaks and recreational activities.